To really improve safety in an organization, the people (all the employees) need to come together and fix the whole system.

This is much more than just a safety issue in an organization. It is a “together” issue.

My Experiences:

Top-Down Organizations

I have been working in various aspects of safety for over 60 years. Almost all the organizations with which I have worked have been top-down managed. This approach has been used by armies, churches, governments, and businesses for centuries. Those in control, at the top, issue the orders and rules, the managers in the middle of the organization are expected to follow and impose these onto the people at the bottom of the organization.

This probably made sense when most of the population was poorly educated and illiterate. But now, here in the USA and other developed countries, this is not the case. Most of the people are fairly intelligent and manage their personal lives quite well. They raise families, buy homes and cars, have complex hobbies, etc. They know how to do a lot of things pretty well.

When these people work in top-down organizations where they are not treated with respect, told what to do, and are pushed around like the interchangeable parts of a machine, they are not usually very happy or productive. Dysfunctional behaviors and troubles like bullying, resistance to change, cutting corners, poor morale and performance, anger, and frustration cause huge losses, like terrible productivity and people quitting.

When safety improvement efforts like bringing in a consultant to fix the safety culture, or to improve safety practices like behavior-based safety, or improve participation are conducted, they often meet a lot of resistance and do not sustain themselves. Most people do not like to be pushed around and treated as if they do not have a brain.

In this environment, it is very difficult to make good safety improvements and very, very hard to sustain the programs. People keep getting hurt and killed.

Partner-Centered Leadership

In working in and leading organizations, I have found that people want to be treated with respect, listened to, share ideas, and learn together. These apply to people in all the various parts of the organization, not just safety.

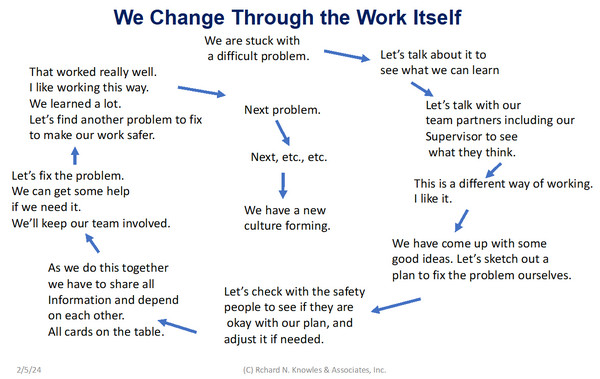

Our Partner-Centered Leadership Workshops include a broad cross-section of people from around the organization and from different levels so that the whole of the organizational system is together for the work. We help people to see their organization as if it is a living system.

As the workshop process develops, the people can see the whole, the parts and the interaction of the parts, which opens-up all sorts of new, creative ideas. Everything is connected to everything else.

As they learn to work together in new ways, they co-create the changes they want to make and a new culture begins to emerge out of the conversations. The whole organization changes and improves, including their safety performance. The improvements are sustained through their ongoing conversations in the days and months after the workshop.

Results

In the big plant where I was the manager, the people improved their safety culture and cut the injury rate by 97% and increased earnings by 300%. We have seen similar changes in companies where we have conducted these workshops.

Conclusion

In highly functional organizations, safety, along with everything else, gets a lot better.

A lot of leaders are looking for the silver bullet to be able to lead in all situations, and to especially make needed safety improvements and to effect extraordinary change. There is a way: it is a framework we teach (Process Enneagram), which works because it is highly principle-based and partner-centered. And, because it is a tool for dealing with complex situations and multiple variables.

We are all familiar with OSHA as both a regulator for Safety Standards and Compliance in the workplace and as an Educator (offering Information and Training across-the-board on the OSH standards). Indeed, if you’ve not looked lately, go to

We are all familiar with OSHA as both a regulator for Safety Standards and Compliance in the workplace and as an Educator (offering Information and Training across-the-board on the OSH standards). Indeed, if you’ve not looked lately, go to

A recent article in the October 13, 2016

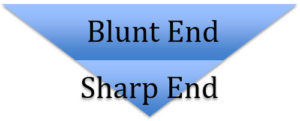

A recent article in the October 13, 2016  This story illustrates so many of the changing conditions and people involved in our work places. Most of our companies do a good job in risk assessments and developing safe working procedures. However, this planning often takes place away from the actual location where the work will be done. This is sometimes called the “blunt end” of the safety process where the people doing the planning do not understand what happens in the work at “sharp-end” where conditions and demands may be quite different, and where most of the injuries happen.

This story illustrates so many of the changing conditions and people involved in our work places. Most of our companies do a good job in risk assessments and developing safe working procedures. However, this planning often takes place away from the actual location where the work will be done. This is sometimes called the “blunt end” of the safety process where the people doing the planning do not understand what happens in the work at “sharp-end” where conditions and demands may be quite different, and where most of the injuries happen. In Erik Hollnagel’s book, “Safety-I and Safety-II” (2014. Ashgate Publishing Ltd., Surrey, UK), he discusses ideas like the significance of the gap between “the work-as-imagined” done by managers and engineers planning and designing the work and the “work-as-done” by the people actually doing the work. This is illustrated nicely by the Ford Star Wars incident where the people doing the “work-as-imagined” failed to understand the actual conditions and mindset of Ford doing the “work-as-done.”

In Erik Hollnagel’s book, “Safety-I and Safety-II” (2014. Ashgate Publishing Ltd., Surrey, UK), he discusses ideas like the significance of the gap between “the work-as-imagined” done by managers and engineers planning and designing the work and the “work-as-done” by the people actually doing the work. This is illustrated nicely by the Ford Star Wars incident where the people doing the “work-as-imagined” failed to understand the actual conditions and mindset of Ford doing the “work-as-done.” Consider the Golden Gate Suspension Bridge (San Francisco) built between 1933 and 1937, an architectural marvel, thought to be impossible because in order to bridge that 6,700 ft. strait, in the middle of the bay channel, against strong tides, fierce winds, and thick fog, meant overcoming almost impossible odds. But it was built, with a grand opening in May of 1937, deemed, at the time of its completion, to be the tallest suspension bridge in the world as well as the longest. A man named Joseph Strauss engineered many new ideas, including developing safety devices such as movable netting, which saved 19 lives; though in all, there were 11 men lost during this construction. Thousands of men – workers of varying ages and from varied ethnic groups – came together to complete this project. (They had to listen and learn to be successful together.)

Consider the Golden Gate Suspension Bridge (San Francisco) built between 1933 and 1937, an architectural marvel, thought to be impossible because in order to bridge that 6,700 ft. strait, in the middle of the bay channel, against strong tides, fierce winds, and thick fog, meant overcoming almost impossible odds. But it was built, with a grand opening in May of 1937, deemed, at the time of its completion, to be the tallest suspension bridge in the world as well as the longest. A man named Joseph Strauss engineered many new ideas, including developing safety devices such as movable netting, which saved 19 lives; though in all, there were 11 men lost during this construction. Thousands of men – workers of varying ages and from varied ethnic groups – came together to complete this project. (They had to listen and learn to be successful together.) Consider the feat of building the monumental Hoover Dam (1931-1936) – a miracle of technology and engineering. No dam project of this scale had ever been attempted before. There were 21,000 people working at that site with approximately 100 industrial deaths. The walls for this structure – that would uphold the weight of the dam – required workers called “high-scalers” who excavated the cliffs, dangling on ropes from the rim of the canyon. Can you even fathom this?

Consider the feat of building the monumental Hoover Dam (1931-1936) – a miracle of technology and engineering. No dam project of this scale had ever been attempted before. There were 21,000 people working at that site with approximately 100 industrial deaths. The walls for this structure – that would uphold the weight of the dam – required workers called “high-scalers” who excavated the cliffs, dangling on ropes from the rim of the canyon. Can you even fathom this? Consider the great Niagara Power Project (1957-1961). During construction, over 12 million cubic yards of rock were excavated. A total of 20 workers died. When it opened in 1961, it was the Western world’s largest hydropower facility. Many people, including from the “greatest generation” and the “traditionalist generation,” worked together on this project. It was a 24/7, multi-year project.

Consider the great Niagara Power Project (1957-1961). During construction, over 12 million cubic yards of rock were excavated. A total of 20 workers died. When it opened in 1961, it was the Western world’s largest hydropower facility. Many people, including from the “greatest generation” and the “traditionalist generation,” worked together on this project. It was a 24/7, multi-year project. Hardly any of us can do our best work all by ourselves.

Hardly any of us can do our best work all by ourselves. When the Safety Culture is right…what do you see? What does Excellence look like?

When the Safety Culture is right…what do you see? What does Excellence look like?